Part II: Practical solutions to the problem of Achilles rupture and the proliferation of injuries to the lower extremities of football players

Andrew ‘Bud’ Charniga

“If you stretch a spring and release it, it will spring back.” R.McN. Alexander, 1988

Figure 1. NFL quarterback fractures right fibula falling from tackle of opposite leg.

You can’t fall safely if you can’t bend

Analysis of such a catastrophic injury as Achilles rupture would be counterproductive if a solution were not offered. Consequently, unlike the irrational (or even none offered) solutions proposed in the literature of athletic training, conditioning coaches and orthopedic surgeons there may be a reasonable, logical alternative course of action to alleviate the plague of ankle and Achilles tendon injuries afflicting football players.

The main differences between the training regimen of the weightlifter and the football player are weightlifters subject the lower extremities to high speed, large range of motion exercises. The preponderance of bodybuilding/powerlifting elements in the strength training of football players and even many of the agility drills do not address the suppleness, flexibility and the dexterity the weightlifting exercises demand and cultivate.

Probably the most important concept to consider is one should not separate or otherwise arbitrarily compartmentalize lower extremity (speaking first and foremost of non – contact) injuries. With the football player’s foot – to – ankles taped, knees taped/braced; hip, knee, ankle and foot joints stiffened by bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and a general lack of full amplitude of motion exercise; a knee injury can simply be the result of taped/spatted ankles and the general stiffness of hips, knees and ankles preventing the athlete from dissipating or other re – distributing the mechanical energy of falling, making sharp cuts while running and so forth.

For instance, consider the following:

“Current thought is that the rising rate of Jones fractures among football players is partially caused by the use of flexible, narrow cleats that do not provide enough stiffness and lateral support for the 5th metatarsal during running and cutting.” Hsu, 2016

A Jones fracture is a fracture of the base of the fifth metatarsal of the foot. A ‘rising rate’ of this type of injury, the proposed etiology and solution are clearly part of one and the same problem. Having the players wear a stiffer shoe to support the foot is illogical. According to this line of thinking the etiology involved with this injury can be due to the foot not being supported by a stiffer shoe to support bending. Consequently, the solution offered is to prevent bending of the foot; or otherwise ‘support it’ (whatever that means), to prevent occurrence of this injury. Sound familiar?

When you combine taping/spatting of ankles, knees, applying braces, even stiffening shoes; stiffening of knees, hips, ankle joints, tendons and ligaments with powerlifting squats to parallel, bench squats, machine exercises and so forth; what will be the outcome? How will joints be able to bend naturally, proportionally, relative to each other; and, by how much?

How can the athlete’s body react to the complexities of moving about the athletic field; be ready to dissipate or otherwise redistribute the mechanical energy of sharp turns, cutting, accelerating, falling and deceleration involved in pursuit and avoiding pursuit with all this stiffness of muscles, ligaments, tendons and joints?

Now consider:

“most biomaterials (this includes tendons and ligaments) have evolved designs which enable them to be tough, so that they can absorb a considerable amount of energy before breaking. As a result, rigid biomaterials exhibit a stress – strain relationship intermediate between brittle and compliant materials. Typically, the maximum operating stress or strain of a biomaterial is much less than its failure stress or failure strain.” Biewener, 2007

According to the above from Biewener, 2007, the “operating stress or strain” of tendon and ligament biomaterials of vertebrate mammals, Cheetahs for instance, is much lower than what would cause such a catastrophic injury as a ruptured Achilles. The ‘normal’ stress/strain forces on this animal are significantly greater than those generated by any football player. This mammal has an elongated Achilles tendon; very lax articulations with approximately 60% of its muscle mass in its back; yet can accelerate from zero to 96 kilometers per hour (faster than a Chevrolet Corvette) in three seconds.

Furthermore, since there are no Cheetah races on the Savannah, these animals achieve these accelerations almost exclusively when pursuing another animal. This of course means they are forced to make sharp cuts; and abrupt changes of direction while tilting to one side to lower body center of mass, i.e., subjecting their tendons and ligaments to even greater forces than linear running up to 112 kilometers per hour.

So, the obvious questions are how and why are ‘tough biomaterials’ like tendons and ligaments blown apart so easily on the football field? This despite the fact, the stress/strain forces experienced in non – contact running, pursuing and avoiding pursuit, have to be significantly less than what would be expected to cause catastrophic stress or strain failures like an Achilles rupture.

The only logical answer to these questions as to why these injuries are becoming all the more peculiar to football is that they are the result of prolonged exposure to strength and conditioning training with a preponderance of bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and techniques coupled with the influence of trainers, doctors, academics and the therapists afforded the players. Over time, these influences predispose NFL and even collegiate football players to the catastrophic stress/strain failures of tendons and ligaments.

Realistic solutions

It is isn’t necessary nor probably practical for football players to train with weightlifting exercises such as squat snatch, squat clean and jerk to receive some of the injury resistance qualities of weightlifters which have been presented. These qualities can be cultivated by applying some not so simple alterations in thinking as regards to training and exercise techniques.

/ reasonable alterations in training methodology.

Reduce the number of repetitions per set in strength training exercises to six or less and eliminate altogether one set to failure. Increase joint mobility by altering the hand and foot spacing on pressing and lower extremity exercises. Eliminate altogether or significantly restrict maximum lifts in bench press and other exercises where form breaks down such as bouncing the barbell on the chest and arching the back to complete lifts.

/ reduce the proportion of upper body bodybuilding exercises which can slow or otherwise make more difficult, cutting and sharp changes of direction by artificially raising body center of mass.

It should go without saying that the NFL test of maximum repetitions with 225 lbs in the bench press is a senseless, worthless test of bodybuilding prowess. Furthermore, training for it is even more counterproductive.

As has been pointed out most of the players on the football field are engaged in pursuit or avoiding pursuit. To avoid a tackle running backs and receivers have to make sharp turns or cuts which necessitates leaning to one side in order to lower body of center mass. This subjects the lower extremities to greater strain than linear running because the athlete has to overcome the centripetal forces of the sharp turns. This is when a number of the non – contact injuries to Achilles and ankles occur. (see part I).

Excessive muscle mass in the upper extremities and chest, above and beyond what should be considered necessary for these players can only be a hindrance to speed an elusiveness. Consequently, the training to perform a senseless NFL test packs on unnecessary upper body weight, raising body center of mass; which is counterproductive to the actual dynamics of the game.

/ drastically reduce or eliminate altogether, taping , spatting and bracing of ankle joints.

A profession where taping joints is the centerpiece of the knowledge base is of course a non sequitur. It does not follow to artificially limit movement in one or more joints in a complex machine like the human body. All the joints in the body are interconnected, interdependent; joint movements are inter – conditional. The mobility of one joint can’t be singled out to restrict mobility without adverse consequences.

/ performing full squats with shins tilting forward should supplant the powerlifting squat technique to become a fundamental means of cultivating strength with suppleness of the lower extremities.

The first step is to determine a rational technique by defining just what constitutes a full squat or deep knee bend. Numerous sources define squat technique; most generally agree on at least several aspects of squat technique:

1/ the knees should not travel past the vertical line of the toes (minimize the forward tilting of the shins and with no mention of bending at the ankle joint);

2/ the muscles involved are quadriceps, hamstrings and gluteus maximus

3/ no mention of ankle muscles;

4/ a full squat is determined by the line of thigh above or below the horizontal;

A fundamental error made in defining the amount of bending in the squat is to use the line of the thigh relative to the horizontal; instead of the disposition of the three main joints: center of knee, hip and ankle. Powerlifting competitions are adjudicated in this manner: “the lifter must bend the knees and lower the body until the top surface of the legs at the hip joint is lower than the top of the knees”. IPF rule book pp17. There is no mention of the ankle joints and it is possible to perform this exercise within the rules with little or no tilting of the shins (involvement of the ankle muscles).

Figure 2. Elite female weightlifter performing full squat with significant tilting of the shins forward. The knees have fully flexed and ankles bent, but the line of the thigh is still above the horizontal and the vertical line of the hip joint is over the heel. This relationship between the disposition of the knee, hip and ankle joints effectively distributes the stress along thigh, hip and shank muscles.

Consequently, one sees the obvious influence of this powerlifting procedure to performance of the squat as a strength exercise in high school, university and professional football weight rooms. By general consensus the squat is an exercise for the hips, quadriceps and hamstring muscles; and, even more to the point; tilting the shins forward is considered bad. Literature from professional organizations describing the squat as an important exercise to develop the muscles of the ankles along with hips and thighs; and, to likewise cultivate suppleness in the lower extremities is non – existent.

For instance, from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) texts:

/ “major muscles involved: Gluteus maximus, hamstrings, quadriceps”

/ “allow the hips and knees to slowly flex, … knees aligned over the feet; keep knees over but not beyond the toes”

/ “continue flexing the hips and knees until the thighs are parallel to the floor”

And, from an NSCA position paper on the squat exercise (Chandler, Stone, 1991):

“Forward lean of the knee increases shear forces on the knee. …’the shin should remain as vertical as possible to reduce shear forces at the knee.” “Maximum forward movement of the knees should place them slightly in front of the toes”.

“The squat exercise can be an important component of a training program to improve the athlete’s ability to forcefully extend the knees and hips…” Chandler, Stone, 1991

From the above descriptions of squatting technique, non sequitur contraindications inclusive; the squat is performed with hip and thigh muscles and ‘allowing’ the shins to shift forward, which in reality strongly involves the muscles of the of the shank; is to be avoided. No effort is made or viable proof offered to demonstrate the ankles should be left out of this exercise. Indeed they refer to ‘forward lean’ of the knee as a precaution as if it it floated in space and was not connected to the shank. How do you ‘lean’ the knee anyway?

One can see from these descriptions of technique, bending ankles together with knees and hips to perform squats are not a consideration.

It is rather astonishing that the ‘scholarly’ NSCA position paper on squats which lists 69 references; does not once mention the following: ankle joint, soleus muscle, tibialis anterior muscle, Achilles tendon, elastic recoil. Furthermore, there is no mention squats are a valuable tool to cultivate suppleness in the lower extremities. Such is the state of the incredibly narrow focus, the profound tunnel vision of textbook land.

Consequently, over time, these ideas unfortunately coalesce into the mainstream of thinking in the training room, classroom, therapy room and so forth. And, therein lies the likely crux of the problem: from high school through college and onward, eight years or more; up until the elite players make it to the NFL, football players do bench squats or parallel – no – shin – movement squatting; because according to academia, the purpose of the squat is “to improve the athlete’s ability to forcefully extend the knees and hips…” Chandler, Stone, 1991.

That is all well and good for textbook land. However, in the real world of running, jumping, pursuit, avoiding pursuit, lifting and so forth, the hips and knees are interconnected with the shank, the feet, and, with all their joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments which nature has set up to bend and straighten concomitantly, inter-conditionally.

It is obvious from the descriptions presented in Part I of players blowing out Achilles tendon in non – contact running as a result of: “forceful plantar flexion and knee extension may overload the tendon causing rupture”, that knee and hip extension pushing against a raised heel is something strange, even dangerous. Forceful knee and hip extension against a raised heel is normal in running and jumping. However, this normal action can become a problem for someone who has been doing no shin movement, minimal ankle bending squats for 8 – 10 years before reaching the NFL.

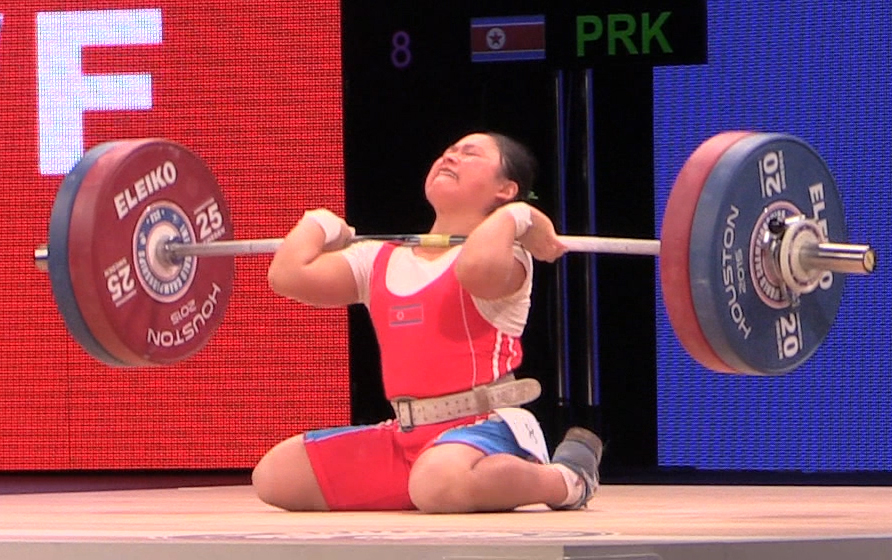

Figure 3. Female 48 kg weightlifter slips and falls attempting to lift 111 kg; uninjured. Charniga photo

Consider the picture of the female weightlifter performing back squats in figure 2 and the accompanying video of the same. This technique of squatting where the shins are actively tilted forward with flexing knees and near vertical trunk incorporates the soleus and other single joint plantar flexion muscles of the shank. These muscles are contracting eccentrically as the Achilles tendon stretches, accumulating elastic/strain energy in the process. When the athlete reverses direction, the aforesaid soleus and other single joint plantar flexion muscles perform what can be described as a reverse – origin insertion contraction. That is to say the origin of these muscles in the middle of the shank moves towards the insertion on the heel.

A typical textbook description of soleus, or gastrocnemius muscle actions show insertion towards origin movements – a heel raise for instance. No one considers these muscles perform the opposite action in squatting, i. e., to straighten knee from reverse origin insertion of soleus in synergy with quadriceps. For instance, biceps muscles are typically illustrated in the textbooks with the hand moving towards the shoulder as in a biceps curl. A reverse origin insertion example for biceps would be a chin up, i.e., the shoulder (where the biceps originate) moves towards the forearm.

Performing the back squat exercise with the form depicted in figure two and accompanying video is obviously antithetical to what is considered the correct form from such organizations as the National Strength and Conditioning Association. This is also true of the overwhelming majority of high school, collegiate and professional strength coaches. Furthermore, the squatting techniques of personal trainers, physical therapists, athletics trainers and others are at best nonsensical; with a host of choreographed restrictions to bending.

A question you will not see raised is how many lower extremity injuries which occur on the court and athletic field can be traced to years of these ‘safe’ squat techniques, combined with taping, bracing and of course, strength training with an amalgamation of bodybuilding/powerlifting and ‘make up’ personal trainer exercises.

Figure 4. A 58 kg female weightlifter bounces three times at the bottom of each repetition with 135 kg squat before standing erect. Charniga photo

The shins can and should be tilted forward to perform squats; with the vertical line of the knee well past the toes. The hamstrings are not involved unless the trunk leans forward significantly. The soleus and other single joint plantar flexors become heavily involved in knee extension when the shins bend forward and back. The knees and ankles should fully flex. However, the line of the thighs can still be above the horizontal in the lowest position.

“The most obvious thing a spring will do is to reverse a movement.” Alexander, R. McN, 1988

Furthermore, the body’s largest, strongest spring, the Achilles tendon stretches and recoils like the spring it is when the athlete reverses direction from the bottom of the squat. Consequently, the elastic properties of the Achilles tendon are enhanced and the recoil of elastic energy is coordinated with the rest of the muscles of the lower extremities; as nature intended.

The lifter in the video accentuates the ankle muscles in squatting; pumping her shins forward and back, piston like, to bend and recover from the squat. Unlike the stilted, mechanical, man made textbook techniques, all the muscles of the lower extremities, especially those in the shank are heavily involved which is consistent with real world conditions of running, jumping, high speed pursuit and avoiding pursuit on the athletic field, and so forth. This is a rational squatting technique. Joints are not artificially segmented with tape, bracing and stifled with arbitrary textbook restrictions on movement of the shin; all the muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints of the lower extremities are actively involved.

/ include dynamic exercises like jumping squats to develop coordination and dynamic suppleness foot to hip, i.e., for the lower extremities to perform as a single leg spring;

The jumping squat exercise illustrated in the video is an excellent alternative to the negative effects of bench squats, powerlifting squats, vertical shin bends, machine squats and so forth. The young woman in the video illustrates how the lower extremities work as a single leg spring in absorbing elastic energy on the downward phase and releasing elastic energy from tendon/ligament recoil in the upward jump phase.

Figure 5. Female weightlifter performs multiple repetition jumping squats with 35 kg. Charniga photos

All the joints muscles, tendons and ligaments of the feet, shank, thigh and hips are interconnected and as such are a single spring. This elastic, dynamic exercise compliments the demands of dynamic sport considerably more than any bodybuilding/powerlifting exercise or technique. The carry over of this exercise to dynamic sports like football is a perfect compliment to squatting in the manner illustrated with accentuation of movement in the shank. This simple exercise enhances strength, power, coordination and suppleness with rather light weights of 40- 50% of the maximum squat.

/ replace stilted small range of motion bodybuilding exercises with large amplitude of motion movements in the lower extremities with light weights or minimal resistance to cultivate dynamic flexibility and suppleness.

For example, the two figures in figure 5 illustrate two contradictory philosophies of how to perform a simple lunge exercise with light resistance. The figure on the left shows the lines of the (from left to right) front shin, thigh, trunk, rear thigh and shank. This technique courtesy of the NSCA comes with these instructions:

“keep the trunk vertical, take a large step forward.

“… move the body more downward than forward until the knee of the rear leg is just above the floor. This will ensure that the front knee will not move beyond the toes of the front foot.”

Just like the NSCA instructions for the squat, the rear leg is bent out of fear of tilting the shin. Their version of the lunge exercise is said to develop quadriceps, gluteals and hamstrings. It is copied verbatim, right from bodybuilding texts. Since the shin of the front leg is not to shift forward the muscles of the shank and of course the ankle joint don’t exist. There is no mention of ankle muscles or dynamic flexibility.

The Russian version of this same exercise illustrated is a stark contrast: rear leg straight, front knee well bent with shin tilting well forward with bending at the ankle joint. The Russian lunge technique is designed to cultivate dynamic flexibility, suppleness and strength in the lower extremities for dynamic sports. The suppleness and flexibility this exercise cultivates comes in handy if one falls or is tackled because muscles and tendons will lengthen with less internal resistance. Consequently, the athlete’s body is better able to react and dissipate the mechanical energy of falling.

The NSCA lunge is a bodybuilding exercise for bodybuilding muscles to look at in the mirror; not for running, jumping and springing about the athletic field. Nominal research on their part and even less imagination was required to come up with this exercise.

Figure 6. Lines in figure on left depict the disposition of the front shins, thigh, trunk, rear thigh and shin of model of lunge according to the NSCA. The figure on the right depicts the proper (Russian) form of the lunge exercise with significant tilting of front shin, flexion of front thigh along with straight back leg and raised heel.

“Coordination is to a great extent determined by the ability to actively relax the muscles”. Y.V. Verkhoshansky, 1988

/ stretching tendons and ligaments by means of relaxation of muscles to cultivate the suppleness transferable to dynamic movements.

There are many constructive examples of effective methods of developing flexibility and suppleness through stretching routines to be found in manuals, books, internet videos and so forth. Suffice to say the example presented in Part I of the football strength and conditioning coach is not one of them.

A simple method of developing suppleness/flexibility for dynamic sports like football, rarely considered if not overlooked entirely is to perform large amplitude of motion resistance exercises with light weights like the Russian lunge, real full squats and so forth. As far as stretching is concerned Yoga techniques are a good model because ‘quiet’ muscle relaxation not carnival barking is the key to achieving good mobility.

One patently obvious shtick on display in university and professional football videos are players straining in the weight room in bench press, powerlifting squats and so forth, i.e., slow movements with prolonged tension; likewise pulling weighted sleds, chains and others for running. These exercises, especially the pulling the weight sleds are not conducive to developing the qualities associated with sprinting, for example.

When a world class sprinter covers 100 m for instance, in 10 sec; one or both feet are on the track for a total of only four seconds. That is to say, the sprinter is airborne for 60% of race. The shorter the time on the track the more power required to execute each step. Furthermore, elasticity and suppleness are important qualities of the high class sprinter because the lower extremities flex and extend through large amplitudes of movement. Internal resistance resulting from stiff joints, muscles, tendons and ligaments would be a hindrance to speed.

Hauling weighted sleds, pushing ground keeper’s carts and the like are in effect bodybuilding runs; with little in common with brief plant time strides of sprinting and are probably counterproductive to develop running speed.

How can you fall safely if you can’t bend?

The high rate of lower extremity injury in football, especially non – contact injuries, and in particular a catastrophic injury like Achilles tendon rupture, unquestionably are caused by the cumulative effects of an amalgamation of chronic, prolonged application of joint, muscle, tendon and ligament stiffening bodybuilding/powerlifting strength and conditioning techniques, taping, spatting, bracing of joints, and so forth.

The frequency of such a catastrophic injury as an Achilles rupture can be at least minimized if not eliminated altogether by:

/drastically reducing the volume of bodybuilding/powerlifting exercises and techniques which now make up a preponderance of the strength and conditioning of football players at all levels;

/ eliminating altogether or drastically reducing the practice of taping/bracing ankles;

/ replace the powerlifting/bodybuilding/personal trainer/NSCA squatting techniques with the technique described where ankle joints bend and shank muscles are heavily involved;

/ stretching muscles, tendons and ligaments with quiet muscle relaxation techniques and large amplitude of movement exercises with light resistance.

References

/ Charniga, A., “Reverse Engineering Injury Mechanism: Achilles tendon Ruptuers and the NFL”, https://www.sportivnypress.com/

/ http://www.powerlifting-ipf.com/rulescodesinfo/technical-rules.html

/ Chandler, J.T., Stone, M. H., “The squat exercise in athletic conditioning a review of the literature”, NSCA Journal 13:05;1991

/ Alexander, R. McN., Elastic Mechanisms of Animal Movement 1988